“Great art is both window and mirror… whether it’s your mask or theirs.”

– The Mask Keeper

Recto

Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 has me feeling conflicted.

Befitting its name, Sandfall Interactive’s debut title is a game of contrasts. There are many bright spots. There are also some not-so-bright spots. I want to quickly cover both sides, and I might touch on some mechanical specifics while doing so, but I’m not going in depth on the story other than to say…

Clair

Writing

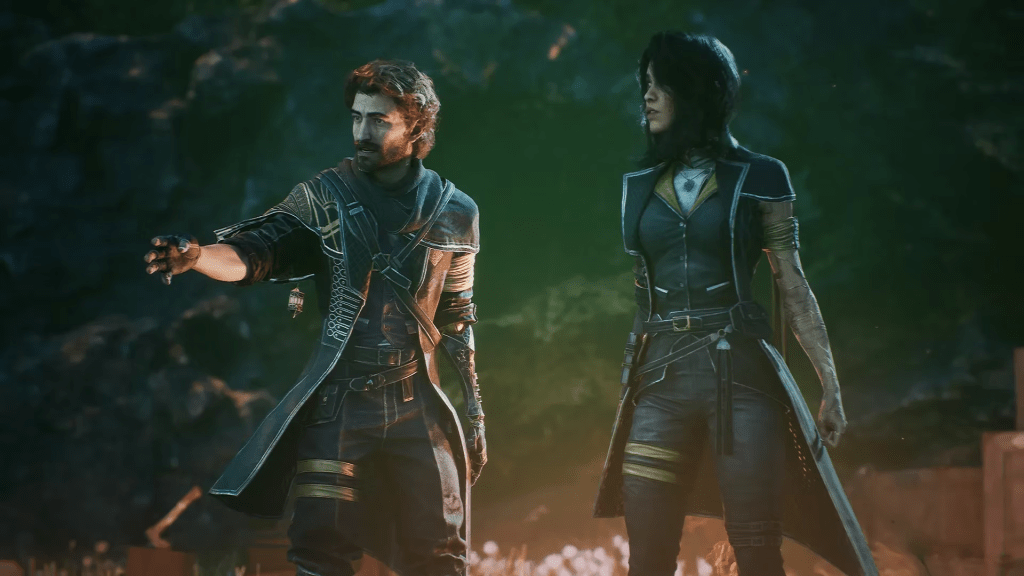

I liked the story, and I like it more the more I reflect on it. It has solid themes centering on how we approach grief. The script, penned by lead writer Jennifer Svedberg-Yen and creative director Guillaume Broche, asks a question of how we should move on from loss and then paints many moving pictures of how one might begin (or fail) to do so.

The game is also concerned with the ways people use their creativity. It weighs in on the responsibilities of artists to their audience, to their work, and to themselves.

Key to the success of the story, the many characters who you meet and assume the role of all feel fully realized. They each have their yearnings and sorrows and joys, their faults and their virtues. What begins as a one-sided conflict develops into a clash of perspectives, one where it feels fair to side with anyone. The morality at play is not painted in black and white—each character embodies a self-justified truth.

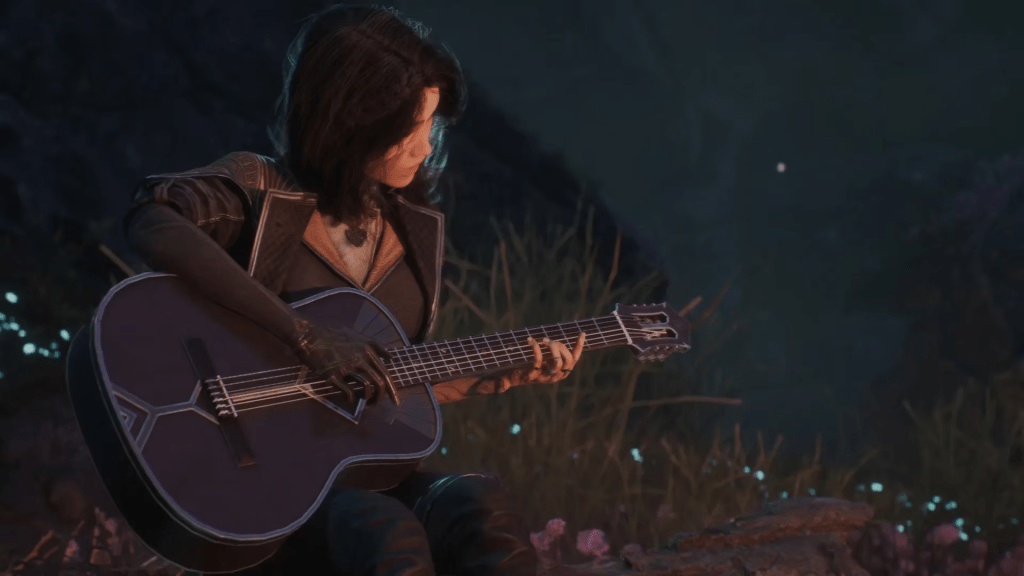

Music

I can’t be sure yet, but I think Lorien Testard’s score will be one of those game soundtracks that sticks with me forever. In the way that I can be walking along and suddenly start humming a theme from Final Fantasy VII, I expect the motifs from Expedition 33 will be just as intrusive.

Remind me to follow up on this thought 25 years from now.

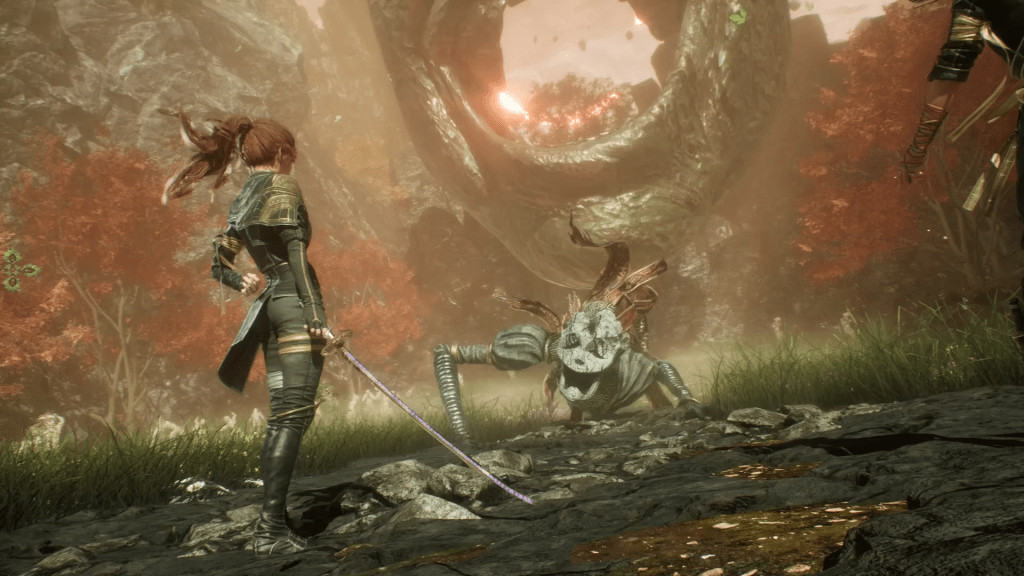

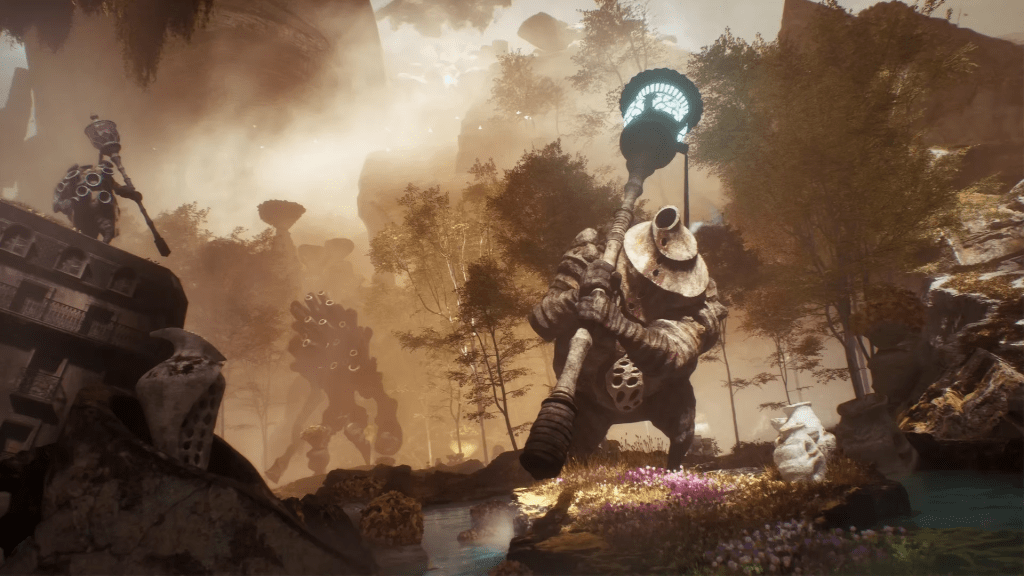

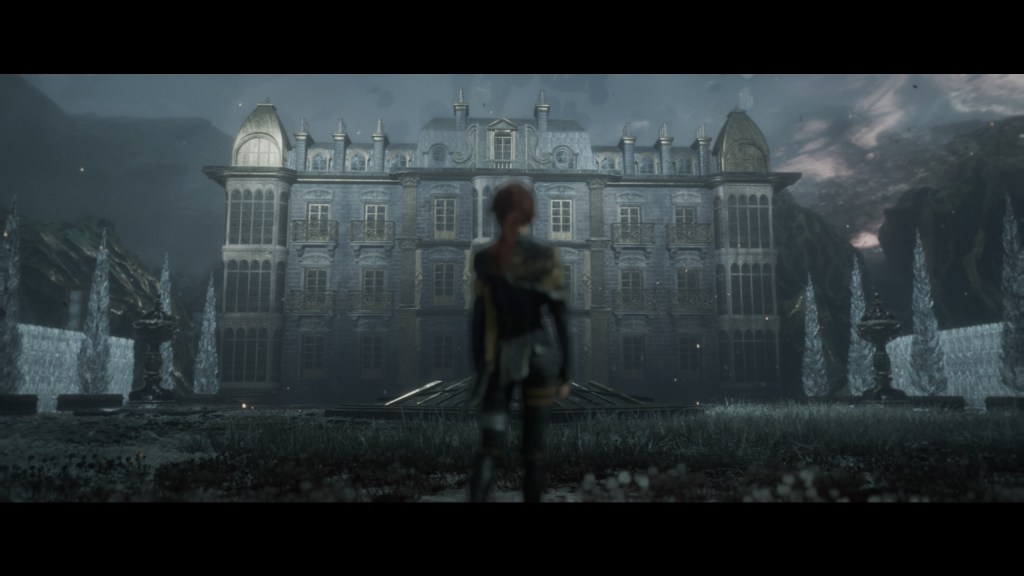

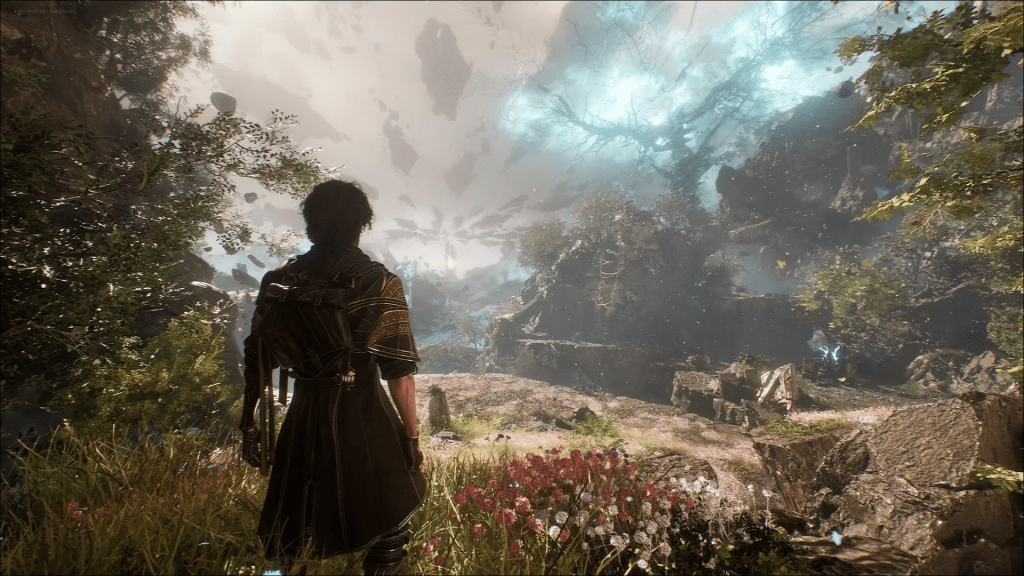

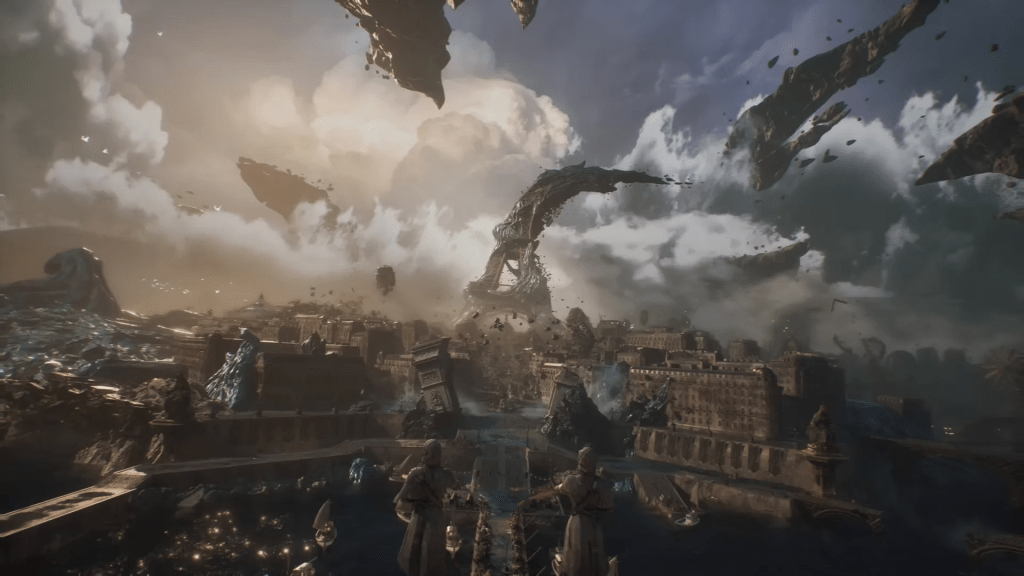

Art style

There are scenes in this game that are worth framing. The character designs are immaculate and flawlessly rendered. And there’s a unity to the overall aesthetic that captures a certain… well.

If you ask someone about this game, they’re bound to mention that Sandfall Interactive is a French studio. Maybe what they should say is that Expedition 33 could only have been made by a French studio. And living in a world where everyone is so obsessed with working, after playing this game I had to wonder if perhaps the French have never stopped obsessing over art.

Combat

I enjoyed the combat in Expedition 33 to a point. Following in the footsteps of one of the true titans of turn-based combat, Paper Mario, there are active elements to each battle. You can time inputs when you’re doing your moves to make them more effective, and when enemies attack you can either dodge or parry them. These active elements add a layer of mastery on top of the general strategy of managing your party.

The game also has great boss fights, and plenty of them, too. There’s a boss in each area, sure, but there are also bosses out on the overworld, special encounters hidden in each level, and super secret bosses locked away behind optional paths. Most bosses have increasingly elaborate attack patterns or some other wrinkle that gives you an extra plate to spin.

Every fight is also rendered with cinematic flair—the developers clearly put a lot of thought into presentation.

The combat in Expedition 33 probably contributed a lot to its positive reception—a game that is fun tends to reach more people. For me, though, combat is also where the cracks start to appear.

Obscur

Balance

When critiquing a game, I make a point of not offering solutions to problems I run into. I try to communicate how I feel and what doesn’t work for me and leave it at that. I am not a game designer. Whatever solution I think of will not have taken into account the dozens of ways it either fails to resolve the issue or breaks other things in the process.

Having said that, I cannot begin to conceive of how you could fix the balancing in this game.

I should preface by saying I played Expedition 33 on standard difficulty, and I found the critical path to be a piece of cake. The only times I suffered real setbacks were if I walked into a boss fight that directly countered my party.

But as soon as I stepped off the path and tried to engage with side content, I would get walloped. We’re talking “walk into an optional boss and explode on contact.”

Sometimes the game would try to warn me away from situations like this with a “Danger!” indicator over the door to an area, so I avoided those places. But “Danger!” only tells me not to go to a place right now. It doesn’t tell me when I should come back. And there seems to be a pretty clear reason for that.

See, the developers have no way of knowing how powerful you are at any given moment, in large part because of the

Systems

In RPGs like this one, you can level up your characters to make them stronger. Battles give you experience, experience lets you level up, and leveling up lets you allocate points into stats. Give your characters more health, or more power, or more speed, or more defense, or more luck—the numbers go up and your party becomes that much more effective.

So, if the game knows I’m level 12, why can’t it tell me to come back to that “Danger!” area when I reach level 30?

Because in Expedition 33, your power is also influenced by your Pictos and Luminas.

In brief, Pictos and Luminas can give your party passive traits, changing how each character behaves in combat. Pictos can also provide significant boosts to the raw stats that are otherwise adjusted via level up (Luminas only gives passives, not stats).

To accurately measure your strength, the developers would have to know which Pictos and Luminas you have found and equipped, and… look, game development is very difficult. Without going further into the weeds, there’s no good way for them to label each area with an appropriate level.

For me, that’s not a deal breaker—it just means I end up exploring more. But I could easily see how it would encourage other people to explore less. And while I’ll run around a map all day, I did hit a hard limit on how much I was willing to experiment with Pictos and Luminas because of this game’s

User interface

During the last Games Done Quick marathon, there was a running meme that says every game is either a parkour game or a menu game. Example: Super Mario Bros. is a parkour game.

Expedition 33 is a menu game, and the menus are not great.

This is what the screen looks like to manage a character.

Where are my eyes supposed to go here? Why does the character model take up so much of this screen? Why is it so dark? I ask that as someone who exclusively uses dark modes.

Here’s what the Pictos menu looks like.

And here’s what the Luminas menu looks like.

If you give me the option to set favorites or filter nodes in a menu, I am frightened. You are sending me the message that I probably want to interact with these menus as little as possible.

I’ve seen some of the crazy setups people pull off in this game, but I so hated these menus that I never wanted to adjust my builds if I could get away with it. I would go in and equip new or better things as I got them, but I was never willing to completely retool everyone’s kit.

It’s probably for this reason that I eventually got tired of the

Combat

I didn’t play this game straight through from start to finish, so I don’t feel confident saying that Expedition 33’s combat becomes less interesting over time. I will say that I became less interested in it.

Which is fine—I just ignored standard enemies in favor of finding those unique boss battles I liked so much. Buuuuuut the farther I got, the more I found that the parrying system I praised earlier was starting to become a drag. Rather than remaining a way for me to gain an edge, it began to feel mandatory for success. That would be fine if parrying felt fair.

It doesn’t always feel fair, though. Far too late I realized that much of the time (but not always?) the sound of an enemy’s attack was more important than the animation. Except the audio queue would vary by enemy and sometimes by attack, too.

As enemies started exhibiting more and more elaborate attacks with increasingly esoteric windups, combat gradually became a completely different kind of test. There’s tension between, on one side, a combat system that wants to test how well you know your characters and how adeptly you manage turn order and, on the other side, battles that are testing your ability to hit hyper-specific parry windows 7 times in a row and oh by the way the enemy has 4 times as many turns as you. Sometimes that shift happens within the span of a single fight.

There’s a world where that’s compelling design. It probably is to some people. I could cut every word in this section and replace it with “skill issue.” But for my money, it just doesn’t feel like the devs fully figured out what they wanted to do here.

Of course, you could always just spec yourself to one-shot every boss in the game, but that requires intimate knowledge and precise management of Pictos and Luminas, which, see above.

Art direction

I know I said that there are many scenes in this game worth framing, but there are other times where I walk into an area and have to blink several times before my eyes can focus on something. And not because I don’t get what the game is going for with its impasto dreamscape of a world.

But there are a lot of environments that feel very tech demo-y. After running through enough corridors lined with the same rock texture, viewing enough vistas where there’s just a lot of stuff floating around, and stumbling into another corner of the map that features the same pile of crates and barrels, it can feel like the edges of the game have been filled out via high-quality asset flipping.

And that’s a shame because while the majority of the game exhibits impressive attention to detail, not all of it does.

Which brings me to

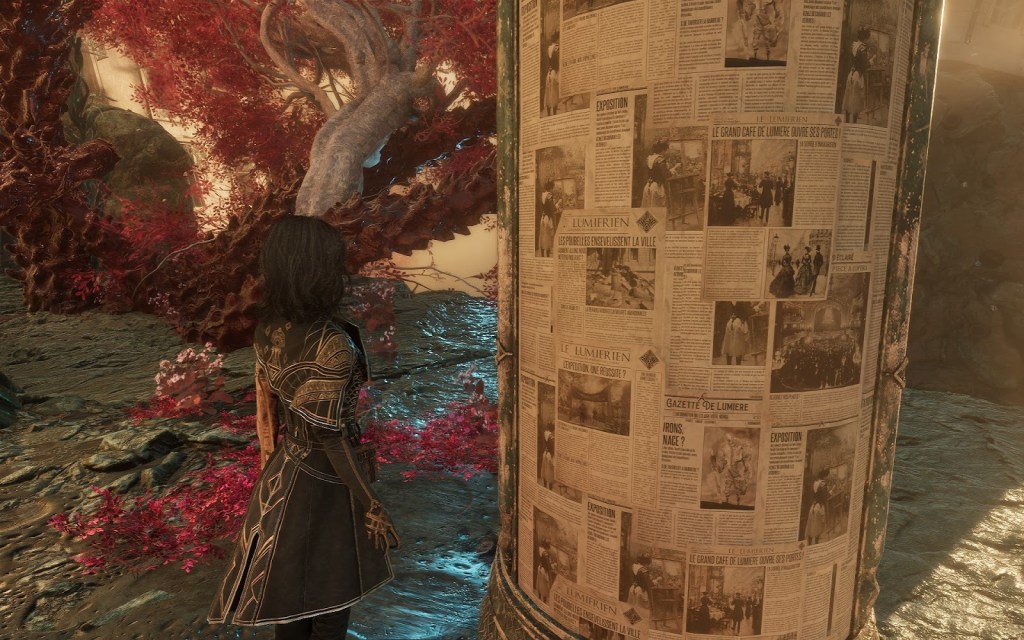

This bulletin board

Look at this:

What are we looking at?

It’s a bulletin board covered in newspapers. Right?

Look closer.

The language is incomprehensible. The layouts are nonsensical. The imagery is confounding.

It’s an older vintage by today’s standards, but this appears to be generative AI—a vulgar artifact on an otherwise pristine canvas.

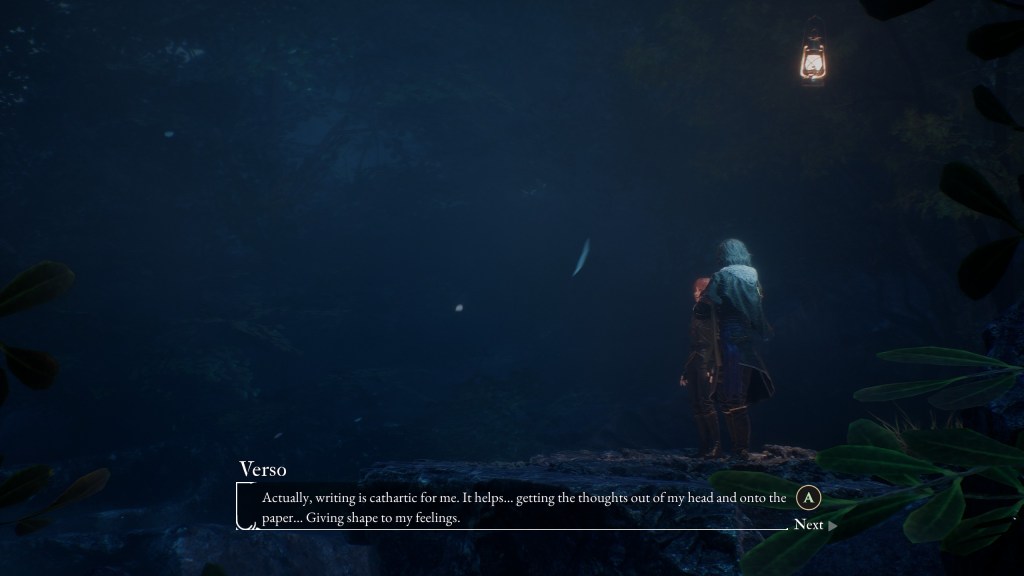

Verso

I’ve buried the lede. This is the actual reason I feel conflicted about Expedition 33. Whatever qualms I have with the menus or balancing or combat philosophy, they all pale in comparison to the way this one art asset bothers me.

And it’s not even in the game anymore. Less than a week after release, Sandfall patched the game. The patch notes for that update include this entry under Bug Fixes:

“Replaced a placeholder texture with the correct visual asset”

Here’s what the bulletin board looks like now:

So why does this thing give me so much pause?

It’s such a small detail, something most people probably run past without a backward glance. And the patch notes refer to it as “a placeholder texture”—singular—which suggests it’s the only such asset that made it into the final game.

Why then? What’s so bad about this?

Come. Crash out with me.

Under the rug

Apart from the patch notes linked above, Sandfall Interactive has never commented on the bulletin board. At the time, the studio had not said anything about how generative AI1 does or does not figure into their creative process.

It’s good that they patched it out. Fixing mistakes is a given. But to phrase it so cagily (“a placeholder texture”) is like confessing to littering when you’ve been accused of arson.

Of note, Steam requires that developers disclose if their game features “Any kind of content (art/code/sound/etc) created with the help of AI tools during development.”

Expedition 33’s Steam page does not feature this disclosure, presumably because the final game no longer contains any content that meets this definition. But you have to disclose gen AI usage when you apply to have your game listed for sale. It’s not clear to me if there’s a box you can tick that says “We’ve used just a skosh of AI, but only for placeholder assets, there won’t be any in the game that people can purchase, we swear.” Maybe that box exists, maybe they ticked it.

Or maybe the people responsible for getting the game listed on Steam didn’t know that gen AI was used to create placeholder assets like the bulletin board.2

Maybe the developers didn’t even know.

And that raises a question.

When is a placeholder not a placeholder?

I work in advertising as a copywriter. Making ads is sort of like making games—they’re both media designed for public consumption. The difference is that video games are a meal you choose to eat while ads are force-fed to you whenever you let your guard down.

But our workflow also has similarities to game development. Case in point, we use placeholder assets all the time.

If we’re reviewing a piece with our team and we know it’s going to feature some copy that hasn’t yet been written or finalized, we fill the space where that copy would go with lorem ipsum. If the piece has a visual element that hasn’t yet been designed, we represent it with a giant magenta box labeled FPO (for placement only).

A placeholder isn’t meant to resemble the thing it’s holding the place of—it’s meant to draw attention to itself, reminding everyone working on the piece that it isn’t done yet, that it still needs some finishing touches.

So when I hear that someone is using gen AI to create placeholder assets, I get confused. It doesn’t sound like their placeholders are doing what they want (or need) them to do.

Again, I’m not a game dev and can only speak to my own experience as a creative. But here’s a thread on Bluesky with a bunch of game devs yelling about this exact thing.

To each their own, I guess? Maybe that original bulletin board is what a placeholder looks like at Sandfall. Or maybe I should be thinking about this in a more granular sense—the whole studio isn’t necessarily implicated.

Small indie studio

The staff page for Sandfall Interactive lists 30 people and 1 dog. It’s a scrappy team of developers led by senior talent that previously worked at Ubisoft. The studio’s homepage says “We believe the latest game-making technologies now make it possible for indie teams to deliver outstanding production value in a realistic 3D graphic style.”

Small headcount or no, it generally takes a lot of people doing a lot of work to make a video game, and the credits for a game like this will usually list a number of support studios that the lead team has sub-contracted work to.3 The bulletin board could have come from an external source.

…is what I assumed in the first draft of this post, but looking at the credits for Expedition 33, there aren’t any support studios credited for art or visual design. There are some contractors credited for gameplay animation, and a few different production partners cited for quality assurance, compatibility testing, and porting.

That still doesn’t mean all of the art was designed in-house at Sandfall. Some of it might have been done by independent contractors whose names were left out of the credits.4 But I’m not trying to sleuth out exactly where this thing came from or who made it, I’m just trying to convey how this could have happened.

Look: there are teams of people within a studio. Within those teams, there are smaller teams. Different teams are assigned different tasks and different people within those teams have their own tasks, all to make the stuff that goes into the game.

With the case of this offending bulletin board texture in Expedition 33, maybe a single person used AI to generate those not-newspapers. Does that excuse the way this has been handled?

Well, not really.

Whether someone contributing to a game is full-time or a contractor, you expect their work to be reviewed by somebody else, probably the person who is leading their team. Whoever was responsible for reviewing the work of the bulletin board designer either didn’t notice that it was made with AI or they didn’t care. And if they didn’t care, then it’s either an expectation or they were told not to care by the person who reviews their work. Follow the chain up and up and up and suddenly this is an institutional issue.

There’s another way this could have gone that I’m guessing plenty of us can relate to. A lot of bosses out there are asking their employees to experiment with AI. You’ve probably heard the spiel: “We’re going to get you a license for this tool. Just play around with it, see what it can do. This stuff is going to change everything, and we don’t want to be left behind.”

Maybe the bulletin board is the result of such an experiment, one that, intentional or not, wound up in the launch build.

I don’t know what happened here. It feels bad to speculate in this way. I feel as though I’m spiraling.

But Sandfall was silent. They called it a placeholder texture, a bug.

Only recently have comments surfaced from producer François Meurisse discussing the studio’s use of gen AI.5 Speaking to Spanish newspaper El País back in June (and reproduced here via Polygon… via Google Translate):

“We used some AI, but not much … The key is that we were very clear about what we wanted to do and where to invest our efforts. And, of course, technology has allowed us to do things that were unthinkable not long ago.”

So that’s an admission, albeit not a direct comment on the situation with the bulletin board. It doesn’t give any sense of what the attitude within the studio is toward AI or what they’ve done to make sure something like this doesn’t happen again, or if they even see it as a problem worth fixing.

And while I loathe that this is the case, with the way things are now, any use of AI begets the question: Where do you draw the line? If you are willing to use AI for something so minor, what won’t you use it for? Call it a placeholder, don’t acknowledge it further, draw no attention to it—it doesn’t matter. It is still a pinprick through which doubt seeps in.

I don’t want the first feeling I have about a piece of art to be one of suspicion. I want to respond to your work with anything other than mistrust.

But with the way things are going, it seems like it’s only going to get harder to feel anything else.

Consulting the oracles

One of this year’s most popular games is ARC Raiders, an extraction shooter developed by Embark Studios, published by Nexon. Embark previously put out another shooter, The Finals, which was also well-received.

Both ARC Raiders and The Finals use AI-powered text-to-speech models trained on the voices of real actors. The developer says this makes their creative process more efficient, allowing them to make updates to the game without the added step of recording new voice lines for characters.

A 2-star review of ARC Raiders from Eurogamer prompted discussion online over how much AI is too much AI in game development and whether its use should be worth such a heavy penalty on a review score.6

In an interview, the CEO of Nexon, Junghun Lee, said:

“First of all, I think it’s important to assume that every game company is now using AI. But if everyone is working with the same or similar technologies, the real question becomes: how do you survive? I believe it’s important to choose a strategy that increases your competitiveness.”

Lee’s thinking here is similar to a number of leaders within the gaming industry. Let’s check a quick roundup from the past several months:

- Krafton is another South Korean publisher whose umbrella includes PUBG, Subnautica 2, and Hi-Fi Rush (after acquiring Tango Gameworks from Microsoft). The company recently announced that it is going “AI first” ahead of an organization-wide restructuring.

- The CEO of Arrowhead Games, maker of Helldivers 2, thinks the conversation around AI should be less black and white. He says that AI content shouldn’t end up in games, but thinks that if a company wants to use it to be more efficient with paperwork, that should be OK.

- Here’s an excerpt from a recent Bloomberg interview with Swen Vincke, head of Larian Studios, talking about the development of their follow-up to Baldur’s Gate 3:

- Vincke has since had to go on the defensive, battling to protect his studio’s reputation. Even knights in shining armor can have their honor tarnished.

- Call of Duty: Black Ops 7 has quickly become one of the worst-received games in a franchise that justified a $70-billion merger between Activision and Microsoft just a few years ago. After people noticed the game featured AI art, Activision released this statement:

“Like so many around the world, we use a variety of digital tools, including AI tools, to empower and support our teams to create the best gaming experiences possible for our players. Our creative process continues to be led by the talented individuals in our studios.”

- Phil Spencer, CEO of Microsoft Gaming, has said there is no mandate for their studios to use AI tools, leaving that decision to individual teams of developers.

- Square Enix has announced a plan to use AI to automate up to 70% of its QA and debugging processes. The goal of this plan is to make those processes more efficient. The Japanese gaming giant has recently made a number of plays for efficiency, most of which resulted in layoffs.

- Yves Guillemot, CEO of Ubisoft, thinks AI is “as big of a revolution for our industry as the shift to 3D” and was thrilled to tell investors that all of their studios have embraced the technology. The company recently had to release a statement when an AI-generated loading screen that was only meant as a placeholder made it into strategy game Anno 117: Pax Romana. Ubisoft has shown that staying on top of hot trends is a priority for them: they previously made a full commitment to the blockchain and NFTs.

- Finally, Tim Sweeney, the CEO of Epic Games (maker of Fortnite and the Unreal Engine), recently tweeted that, actually, Steam’s AI disclosure policy “makes no sense” because “AI will be involved in nearly all future production” for games. He added: “Why stop at AI use? We could have mandatory disclosures for what shampoo brand the developer uses. Customers deserve to know lol.”

The more you listen to these kinds of people, the more you hear the same things. They all say “this is the future” and “you can’t put the genie back in the toothpaste tube” because, knowingly or not, they’ve all been convinced to hold water for the companies that are selling them these AI platforms. Saying that AI is here to stay is buying into marketing. It is not acceptance but acquiescence—not realism but a retreat from reason.

Some of them go on about how thoughtfully they are using AI, but talking about thoughtful use of AI is the fastest way to hollow out your credibility. Instead of being thoughtful, they ought to be honest. They don’t want to be thoughtful, they want a shortcut that obviates the need for thinking.7

A recent study says that 87% of people in c-suite jobs are using AI on the daily, compared to 47% of managers and 27% of rank-and-file employees. These execs are even using it in their home lives.

It doesn’t take much imagination to consider why they have become so obsessed. The kind of self-styled strivers who wind up in the corner office fear falling out of step with anyone richer than them. They all think they’re part of the same fraternity, the Alpha Capital holders, those whose vast wealth could only be accrued by equally vast wisdom. And right now, none are richer, none more convinced of their raison d’etat than the “Architects of AI.”

To wit, the PAC that sprang up this year and has already raised $100 million to fund pro-AI candidates in the 2026 election is called “Leading the Future.” It’s not often that a Cult of Personality has none, but these technofeudalists are determined to cement their death grip on the economy and society along with it.

However, the more immediate problem with the entire executive class parroting tech industry boilerplate is that because they’re in charge, some people will listen to them. Thus, the myth of AI’s inevitability and omnipresence is perpetuated.

The curse of normality

In episode 2 of Pluribus, after most of humanity has joined a hivemind, protagonist Carol Sturka meets with some of the other survivors—those, like her, who were immune to the biological vector of joining. After sending their chaperones out of the room, Carol turns to the others and asks what they’re going to do about their situation. How will they fix this mess they’re in and save humanity?

To her intense frustration, none of the others see the problem.

Their family and friends have all adopted the same patterns of speech. They all have the same body language. Joined as they are, the hivemind has instant and total access to the collective knowledge, memory, and skills of everyone else on the planet (including the recently deceased). And they are universally gentle and polite, willing to wait on Carol and the others hand and foot.

Carol, a writer by trade, tries to explain that individuality is dead and with it creativity and expression. Those relatives that have become joined are not themselves anymore. They’re everyone else. Everything personal and special, every gift and flaw is lost, blended up and stirred into the psychic soup unwittingly served to everyone outside the room.

Her opponents cannot be convinced. They look at their partner, their aunt, their child and still recognize them. Some wish they could be joined, too. Others express their preference for the way things are now. “Peace on earth,” as one man puts it.

While the anointed thought leaders of the world speak breathlessly about what will be possible with gen AI, my close friends and I talk about it in the same breath as the metaverse or cryptocurrency. I would prefer to dismiss it for the grift it is, but the problem I run into is that it’s already way more normalized than Silicon Valley’s prior pet scams.

The barrier to use is comparatively low, which is surely a factor. I never met a soul who was serious about the blockchain, but most large language models are glorified chat bots, easy to access and easy to use. It doesn’t take a computer science degree to use image generators or text-to-speech, either.

And so, I keep running into people who have not just tried it but use it regularly.

Over Thanksgiving, my sister-in-law confessed that she uses ChatGPT as a detector for other AI content, like “Is this thing my dad or brother just sent me real?” I tried to tell her that an LLM doesn’t know any better than she does, but I didn’t press the issue.

A friend of mine said he uses an LLM at work sometimes but only for extremely menial tasks. The examples he gave were writing SQL prompts and drafting letters of recommendation for the dozenth intern that has passed through his office—stuff that isn’t really part of his job description.

My esthetician told me she used AI when she was making updates to her website. Looking at the homepage now, I can see the bot’s fingerprints, but the copy is a straightforward listing of the services she offers and some value propositions.

What am I supposed to say when people tell me these things?

I could talk about what’s lost with each of these use cases—the personal touches that are withheld when a task is given to AI, the satisfaction of struggling toward a solution, the comfort that comes from facing another’s fallibility and imperfection—but do they need to know how sharp my axe is, or are they just trying to have a conversation?

When people treat AI like a tool with a narrowly defined purpose instead of trying to use it for everything the way the AI companies want, should I hold it against them?

Another friend of mine has joined a Discord server where people can share their creative writing and ask for feedback—anything from a quick thumbs up/down to full line edits. This friend has told me a number of stories about his interactions with people in this community, and after listening to him, I’ve realized a couple of things.

First, forum culture (and forum drama) is alive and well in Discord communities like this one.

And second, creative writing classes like the ones I took in college would have been unbearable if they seated people like the guys my friend vents about. From what he describes, it sure sounds like there are a bunch of trolls who show up to any conversation about writing desperate to find even one person who will give them permission to use AI in their writing process.

These dudes (they always have he/him pronouns) rock up and make strident declarations about how they need to use AI to visualize a character or solve their writer’s block or pen the first draft of their novel (the first of seven they have planned). All of them talk at length about how many incredible ideas they have… and they are unanimously baffled when they hear crickets in response.

Because, to state the obvious, they can’t be trusted. They don’t offer to give feedback, but you would be a fool to accept it even if they did—it’s all but guaranteed that they will feed your work to the plagiarism machine. Not only do you get vacuous, imprecise feedback as a result, but now your writing has been claimed by the slop repository.

The thing with my buddy is he fucking loves writing, so he felt like he had to do something about this. He would talk to the trolls, trying to interrogate their motivations and expose their bad practices, perhaps hoping that they would see the error of their ways and recant their use of the tech. I think he has since come to understand that it’s not his responsibility to disabuse these people of their delusions.

But it makes me wonder, alongside my own anecdotes, if we’re in the same situation as Carol Sturka—hands on hips, asking ourselves what we’re supposed to do if nobody else wants to be saved from this threat.

Tomorrow comes

I’m not certain that the bulletin board from Expedition 33 was generated with AI. I’ve looked for definitive proof, but every time I search I just find people arguing over whether it is or isn’t.

Most people who play the game will never know that particular bulletin board used to look different. Those who do know might not be bothered by it. I’m not here to say they should be.

Nor am I trying to say the whole game is ruined. I still think it’s great, and I don’t think that some sloppy newspapers tarnish Lorien Testard’s scoring or Alice Duport-Percier’s vocal composition or Jennifer Svedberg-Yen’s writing or any of the actors’ performances or all of the excellent work done by the many humans who helped make the game. I’ve watched videos and read interviews with the developers, and they seem like genuine people who are devoted to the craft.

It would not surprise me at all to hear that the bulletin board, this nigh imperceptible blemish, was just an unhappy accident.

And still I am bothered.

Why? Why get so worked up?

Earlier this month, the company I work for held a global meeting during which the executive team talked about the ways we’re using generative AI to bolster our client services.

A few days before that, there was an all hands meeting for my agency’s creative department. On that call, I listened to the executive creative director talk about how important it will be to take every AI training seriously moving forward. He urged us to use every tool at our disposal (and he said they will know if we’re not using the tools we’re given access to). He likened this moment to the shift from print to digital and spoke of people he knew back then who hadn’t embraced the future, saying they all “matriculated”8 out of the industry in the wake of change.

“We all need masks.”

– The Mask Keeper

I don’t think I’m good enough at what I do to stand against what is coming.

Don’t mistake me: I am good at my job. I get the work done and am made to feel like that work is valued.

But I don’t know if I’m so good that I could look my bosses in the eye and say I don’t need these tools. I’m not a better copywriter than some of the people who are already raising their hands asking for access. I don’t have the standing to raise my voice and convince everyone to follow me to the life boats. I worry that if I express my concerns about how AI is decimating this profession it will just mean I end up cut loose quicker than the rest.

I’m in a similar situation when it comes to other people. If you use AI, I will not claim to know your heart. I do not know better than you if this technology makes it easier for you to get through the day. You are the expert on your lived experience. You don’t need me to tell you that I disapprove, and my quarrel is not with you.

But god dammit do I need your help.

Because I am not willing to cede any ground to AI where art is concerned.

AI art—writing, music, visual, any kind of multimedia—is entirely inessential; it lacks essence, the stuff that comes out of us, that we put into whatever we might create. An AI model cannot create; it is the furthest thing from being creative. By design, it can only predict and approximate where to place a pixel, which word it should use, what pitch to imitate. And it only guesses on the basis of what it has been trained on, although “training” is too polite a word for the pilfered material ingested by a model.

It is an Ouroboros born of overreach. The embodiment of the focus-grouped media product, the logical endpoint of by-committee, mass-produced content. Something made by no one cannot be for anyone. Calling this output “art” is impossible. And left unchecked, it will make the continued creation of true art impossible, too.

Everything is compromised. I’ll say it as many times as I have to.

If we allow for further compromise by letting AI play a role in the creative process, we admit that we don’t care about the degrading effects of this technology. The way it steals the work of others, the way it harms those who use it just as much as those who don’t, the way its mandated use is a complete misunderstanding of what makes creation worthwhile to begin with. It ruins everything it touches, and it exists only for the enrichment of the very worst people.

And I would be remiss not to add: It just fucking sucks at what it’s supposed to do. The threat it poses is all the more galling when we look at its abject failure to produce anything compelling, anything that does not expose its inherent wrongness. Nothing but uncanny, brain-smoothing technicolor yawning.9 The most damning thing about people willing to create with AI is that it signals a fatal lack of taste.

This whole thing has been an exercise in trying to express what feels like an increasingly bitchy opinion, but this is a time where articulating that stance feels ever more urgent. So I reserve the right to fly off the handle when AI encroaches on something I would otherwise enjoy. I will wag my finger and stamp my feet because a line has to be drawn.

I say this despite how tiring it is to constantly be on guard. Maybe that is the worst thing AI has done so far—making it so that I cannot engage honestly with anything for fear that it is not being entirely honest with me.

Even so, people aren’t going to stop making stuff—the ones with the inclination can’t resist the urge. So the way we win, the way we save art, is by supporting those artists, any way we can.

That might mean reevaluating a Disney+ subscription in wake of Disney’s billion-dollar deal with OpenAI. Maybe it means taking a hard look at your Spotify subscription after the service recommends another chart-topping AI single to you. It certainly means giving even more scrutiny to the conditions that give rise to the games we play.

In this particular case, it means talking about how much more I would like this game if I didn’t have to write 5000 words about the one part I hate.

Most of all, I think it means seeking out and supporting good work made by good people. If we can do that, maybe we can save everyone else, too.

- Later I’m going to shorten this to gen AI, and eventually I’m just going to call it AI, but for the purposes of this piece, I am always talking about generative AI. Also, hi, this is a footnote. If you would prefer to read straight through without checking these, you should be fine. Most of them are just asides that would otherwise break the flow. ↩︎

- Expedition 33 was published by Kepler Interactive. ↩︎

- It also usually takes a lot of money, but Sandfall also claims the budget for Expedition 33 was less than $10 million. ↩︎

- This is a common problem within the wider games industry. Names often get left out of credits for petty reasons, such as if a developer leaves a studio before the game is released. It’s bullshit—everyone who works on a game should be in the credits. ↩︎

- Not to bury another lede, but these comments were only reported after the Indie Game Awards rescinded 2 awards from Expedition 33 upon learning of Sandfall’s gen AI usage. ↩︎

- As you might expect, plenty of this discourse was fomented by rage-baiting grifters who sidestepped the AI issue entirely to claim that “political opinions” don’t belong in game reviews. ↩︎

- And coincidentally eliminates the need to pay the people who would do that thinking. ↩︎

- I think “percolated” is the word he was looking for? Hard to say. He got his start on the art side of advertising. ↩︎

- Look up “technicolor yawn” if you don’t know what it means. I learned recently and feel like it’s too apt a term for what comes out of AI models. ↩︎

I am seven games into the Trails series (which is at fourteen games and counting) and planning to start the eighth in January. They’re really wonderful games filled with details and unique spins on so many aspects of JRPG development. The dev just made this revelation public a few days ago lol:

https://www.eurogamer.net/falcom-is-the-latest-developer-to-buy-into-the-ai-hype-machine

A friend of mine makes bitsy games in their spare time and when we were discussing AI, they said “you would have to torture me to get me to admitting I use AI” (they don’t.) Its crazy to me to see companies just be so open about this, to not see it as a problem and to not see how large of a group don’t want anything to do with it.

Excellent piece. I haven’t played E33 yet (due to the fourteen part JRPG series thing mentioned earlier); its on my to do list in the next few years like Metaphor was. Sucks that this has been around my periphery as well, because it seems like a real treat otherwise.

Heard Pluribus is excellent.

LikeLike

One justification I read is that the companies that are loudly touting their pivots to AI are doing so to either court or retain investors. They need to show that they’re committed to innovation or risk losing their funding.

If that’s the case, how much bad press does it take to flip that on its head? So that the money people run for the hills at mention of AI instead of the reverse.

Either way, I don’t get it. There’s a certain type of person who so badly wants people to know how much they use AI. I don’t know what they get out of it.

The game is still worth playing, though. And Pluribus is great. Just very solid plotting and character work without any kind of mystery box.

LikeLike